Non-Intentional Meetingd

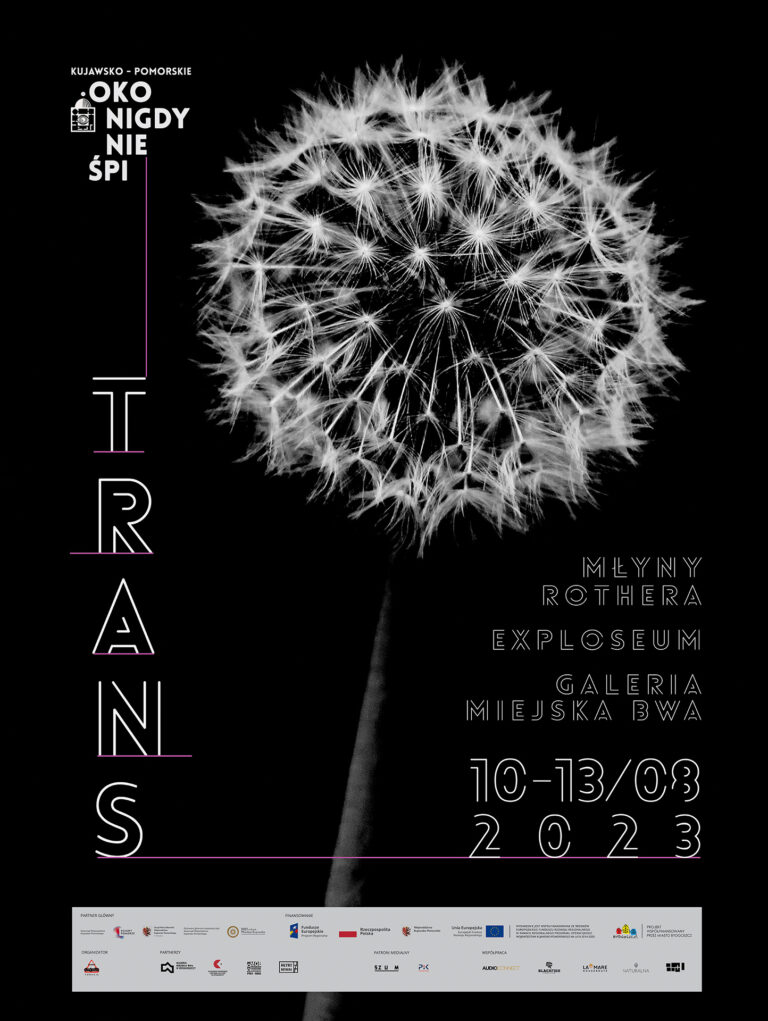

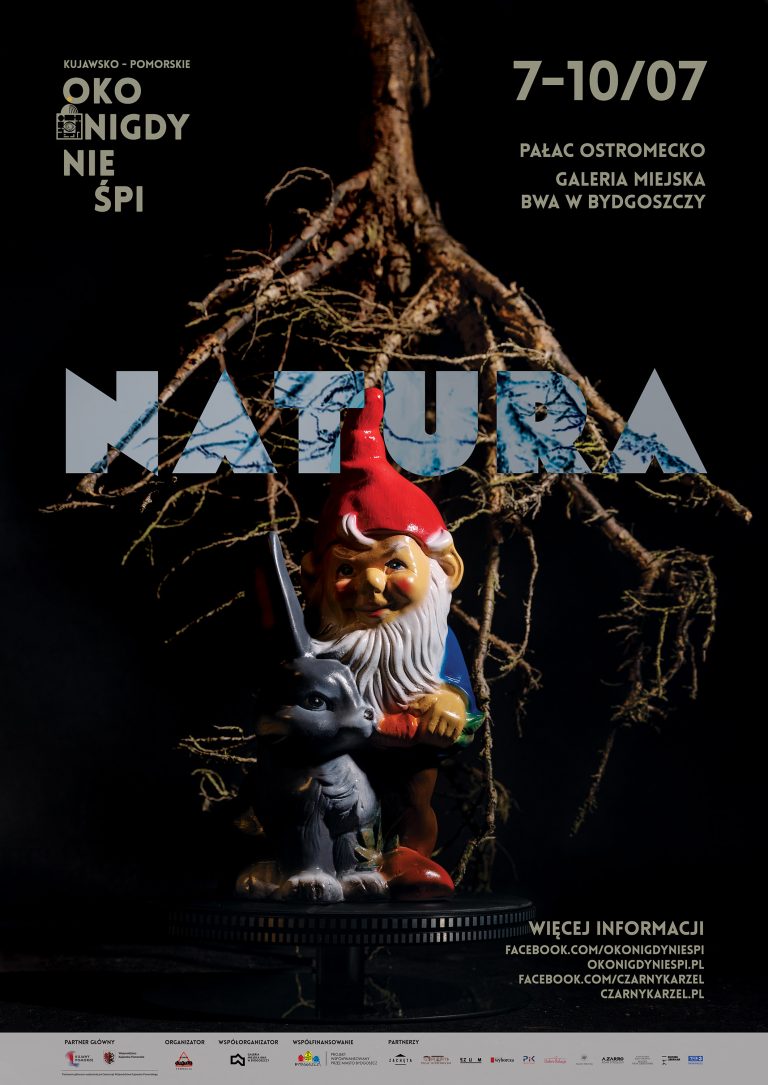

The Eye Never Sleeps – Kuyavian-Pomeranian 2021

“THE MIRACLE”

8th edition

18–21.06.2021

Place: Palaces and park complex in Ostromecko/ Municipal Gallery BWA Bydgoszcz

This year the International Non-Casual Meetings THE EYE NEVER SLEEPS – KUJAWSKO-POMORSKIE will once again face a new topic, although the most up-to-date one… “THE MIRACLE” is a concept from the borderland of mysticism and the most real reality, which we all have experienced during the last several months.

Every day of our lives has been a day in which “enduring”, in spite of great adversity, has qualified as an event from the realm of the “impossible”. “The miracle” is ingrained in our world as an “unreal” event, even though we experience its incredible aura every day. It is enough to look at any object, a tree, a painting, a play, a person, or existence itself to think that we are dealing with a manifestation of the miraculous.

Experiencing the miraculous and exploring and perigrinating the area of the notion of “THE MIRACLE” will be, as every year, the work of distinguished Polish and foreign visual artists, within the framework of the next instalment of the International Non-Casual Meetings The Eye Never Sleeps 2021.

THE EYE NEVER SLEEPS – KUJAWSKO-POMORSKIE will visit the BWA Municipal Gallery in Bydgoszcz and the Municipal Cultural Center in Bydgoszcz, while the majority of festival activities are planned in the Palace and Park Complex in Ostromecko.

The organizers and participants cordially invite you to take part in the “live” event. Below you will find two ideological texts about OKA 2021, authored by Prof. Zbigniew Mikołejko and Grzegorz Brzozowski.

Below you will find two ideological texts about OKA 2021, authored by Prof. Zbigniew Mikołejko and Grzegorz Brzozowski.

„THE MIRACLE”

prof. dr hab. Zbigniew Mikołejko

A miracle is not just a religious phenomenon. It is something much broader. Something that suddenly and in an extraordinary way enters all spheres of existence. It shines with its brilliance but it happens also that it destroys, shatters and radically transforms them. Thus a miracle knows no boundaries, it is an impossibility beyond the circle of possible things and affairs, the ordinary and familiar in our everyday existence. This is also expressed in everyday language, when it makes use of the concept of a miracle to deal with something that in fact cannot be dealt with – with various inexplicable events and experiences, with everything that surprises and shocks us with its uncanny meaning, escaping all our vocabulary and all rational and logical thoughts. A miracle, therefore, refers above all to an exception, which can be seen even in banal and hackneyed expressions – when we use the adjective “miraculous” as a synonym of the phrases “extraordinarily beautiful,” “beautiful to behold,” “incredibly beautiful. If we assume, following Ludwig Wittgenstein, that “the limits of our language are the limits of our world,” then a miracle signifies that it is – also when it does not concern matters of faith – something outside our world. It is a separate existence from this world, radically transcending all of its dimensions and therefore endowed with an extraordinary power that is also terrifying. But it is always paradoxical, “contradictory” to what we know, to what we usually experience. “It is said,” thus wrote the great philosopher and theologian, St. Thomas Aquinas, in the thirteenth century, “that something is a miracle when it happens outside the order of all creation. St. Thomas, a great lover of systems and classifications, also recognized that there are three varieties of miracles: miracula supra naturam (supernatural miracles, such as resurrection), miracula contra naturam (miracles contrary to nature, occurring when nature behaves differently than usual, such as in the case of levitation or stepping stones), and miracula contra naturam (miracles contrary to nature, occurring when nature behaves differently than usual, such as in the case of levitation or stepping stones). miracula praeter naturam (miracles performed by nature, but in a manner determined by its Creator – e.g., healing). This, of course, refers to Catholicism and is associated with the elevation of blessed and saints to the altars. Today, therefore, it is accepted that each of these three types of supernatural signs is sufficient for beatification or canonization, but the miracle need not occur during the life of the candidate for the altars at all. After all, the Church requires two separate miracles: one for beatification and one for canonization, after the deceased has been beatified, with martyrs for the faith “exempt” from the requirement of the first miracle. But the concept of a miracle does not apply only to Catholicism – it is characteristic of many religions, sometimes to a limited degree (for example, Buddha and Muhammad, unlike Jesus, did not use miracles as a means to lead to faith). The power of the miraculous was particularly striking in ages past, in the “first childhood” of humanity. In pre-modern times, when the incomprehensible phenomena of nature and the breakneck adventures of fate were perceived as an enchanted, magical, “sacred” reality – as a great unity of gods, nature and people, which could be explained only in the language of myths, rituals, symbols, stories and poetry. Such an understanding of the sacred, the sacrum, which closely linked holy terror (tremendum element) with holy awe (fascinans element), was very clearly revealed in such a circle. Modern science and technology, beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries, “disenchanted” this world. It was first, through great discoveries, an incredible adventure of humanity. “Miracles of science” replaced the miracles of magic and faith. With time, however, the incredible progress of knowledge became incomprehensible to ordinary “bread eaters”, and the adventure of science turned into the work of many teams, often craftsmen bored with their shallow work, as well as into a kind of “Tower of Babel” in which one physicist does not understand the other, one biologist another biologist. Holiness, too, began to be treated in the West as an area of friendly delight, happiness and spiritual pleasure, a healing therapy. And it is supposed to emanate from itself only goodness and not to be associated with prohibition, the sensation of evil, tragedy or horror.

In our minds and hearts, however, there is still a longing for the “enchantment of the world” again, for the “second childhood” of mankind, which is expressed by the culture, especially the “pop” culture, which builds – like the old ones – its mythical stories, its fantasy stories or horror stories. This is how the stories of Tolkien, Rowling, Chambers or Lovecraft become holy books of our time, and the reality of The Matrix, Star Wars or many computer games – a virtual space of our intimate mysticism, our private rituals and expectations of a miracle. And, of course, the return of an imagination that is naive in its own way, childlike, susceptible to the urges and follies of fantasy. So we hunger for the miraculous, we hunger for a new miraculousness – as if on the measure of our very “unholy” times. Times in which, even from the religious point of view, a true miracle is not a physical, external phenomenon, but takes place within man – as a miracle of grace, of purification, of contrition for sins, of conversion, of transformation. This, of course, frees him from the pressure of science, from its logicality, experientialism and determinism. But it also seals it in people’s minds and souls, makes it something private, intimate, alien to others.

„THE MIRACLE“ – Grzegorz Brzozowski

In the case of a miracle it is impossible to speak of regularities – the very presence of a miracle is a fundamental paradox – being accessible to our senses, it escapes our understanding. Instead of proposing a program of miracles for the upcoming festival, let us look at it rather as a space open to paradoxes – where the possibility of a miracle will appear, though without its guarantee. For the paradox also concerns the frequency of the miracle’s manifestation. It is supposed to be that which is most exceptional – extraordinary, close to epiphany, or at least to being thrown out of the natural order. The concept of a miracle is often close to Rudolf Otto’s image of the sacred as mysterium tremendum et fascinans – going beyond our understanding, a miracle is both delightful and terrifying. As such, it should be the rarest of phenomena. Yet miracles seem to have a lasting impact on our time and our space. We find them not only in the realm of institutionalized religion – for example, as shrines established at sites of apparitions – but also as miraculous springs whose influence remains lasting regardless of religion, offering explanations for their properties. Miracles cut across religious divisions – they elude those who wish to claim a monopoly on them. Miracles are supposed to manifest themselves not only in the communal landscape but also in history – to decide not only about the course of battles (e.g. Warsaw) but also about the very existence of a sovereign community – regaining and preserving independence. Thus miracles seem to affect both our collective and individual bodies. In Mickiewicz’s invocation, after all, it is miracles that are supposed to make us return – whether “to the bosom of the fatherland” or as “a child to health” (and General Dabrowski appears in Lithuania as one whom “heaven has pronounced a miracle”). Miracles become a vehicle for returning to a state of wholeness, life, idyll, paradise on earth, or at least the hope that this state is not ultimately lost. Perhaps, however, miracles are valued by those who have lost the most – faith in them is an expression of radical hope growing out of despair? If in the context of our culture we can speak of the recurring, permanent presence of a miracle, in the case of contemporary culture we may even be dealing with its omnipresence. The miracle is now what we seem to expect constantly, in almost every area of life. The word “miracle” has become democratized, easily passing into the language of (self) promotion, guides, and guides not only to landscapes but also to life. Judging by a cursory review of titles available on the market, we expect miracles not only from saints, but also in the realm of: nature, technology, architecture, unesco, we count on the “miracle of coconut flour” or the “miracle of ph balance”. We do not lose hope either for a communal miracle (“the economic miracle in Poland”) or for a radically private one (“the diet miracle”). Could this mean that we live in miraculous times, or on the contrary: since hope for miracles grows out of despair, perhaps the universality of the expectation of a miracle testifies precisely to the darkness of our times? Do the miracles with which we are surrounded retain any value? When might they devalue? How to distinguish “supposed” miracles from authentic ones? How to win at the exchange of miracles – does the greatest fraudster triumph here? Or maybe the real miracles must remain the most inconspicuous ones, because their value is self-contained anyway – it does not need advertising, audience or applause?

Religious systems seem to resolve this issue by introducing their criteria for the veracity of miracles, thereby establishing their selection and hierarchy. In Catholic Christianity, as Joachim Bouflet wails, a miraculous experience alone – even a smell wafting over an undecomposed corpse – though supernatural, is insufficient to testify to the holiness of its source. Perhaps, however, it is incumbent upon us to maintain the sensitivity to perceive a true miracle – as Wisława Szymborska notes in “The Fair of Miracles”: “A miracle, just looking around: an omnipresent world”? But what is really at stake in this effort – the search for the miracle, distinguishing it from the miracles? Do we need faith in miracles, or on the contrary, is it disbelief in them that sets us free? According to C.S. Lewis, the creator of the miraculous allegory of spiritual transformation as the world of Narnia, those who exclude the possibility of the miraculous open the door to radical materialism: they want to see the laws of nature as inviolable. But where – in such a defined world – will there be space for our individual, determinism-free decisions? On the other hand, the presence of miracles can also be an instrument of coercion. It is experienced by Jesus himself in the “Gospel of…” proposed by Jose Saramago. He is not an independent miracle worker – he is rather surprised by the miracles that accompany him, until they turn out to be a kind of blackmail tool from the omnipotent creator, forcing Jesus to enter the role of savior. Miracles here become, in a way, a tool to humiliate humanity – to keep it from believing that it can try to be responsible for its own destiny: “a miracle in itself, no matter what we are told, is not a good thing, if one must distort the logic and order of things to make them better.” Thus a miracle, like love in Sęp-Sarzyński’s work, in a way entangles us in a trap: and to believe in it is hard, not to believe is a miserable consolation. One of Fellini’s masterpieces – associated as a specialist in films about tricks, fabricated miracles and miracles – opens with the figure of Jesus appearing in the sky, approaching Rome. It quickly becomes apparent that this is merely a helicopter-carried sculpture. Regardless of the unmasking, the paparazzi set off in pursuit of the statue. No matter how questionable the miracle itself may be, the search for it and the awe of it remain authentic; perhaps they are the ones who mark the way to the “sweet life”?